Comments due by Mar. 23, 2018

The

extinction of species by human activity continues to accelerate, fast enough to

eliminate more than half of all species by the end of this century. Unless

humanity is suicidal (which, granted, is a possibility), we will solve the

problem of climate change. Yes, the problem is enormous, but we have both the

knowledge and the resources to do this and require only the will.

The

worldwide extinction of species and natural ecosystems, however, is not

reversible. Once species are gone, they’re gone forever. Even if the climate is

stabilized, the extinction of species will remove Earth’s foundational, billion-year-old

environmental support system. A growing number of researchers, myself included,

believe that the only way to reverse the extinction crisis is through a

conservation moonshot: We have to enlarge the area of Earth devoted to the

natural world enough to save the variety of life within it.

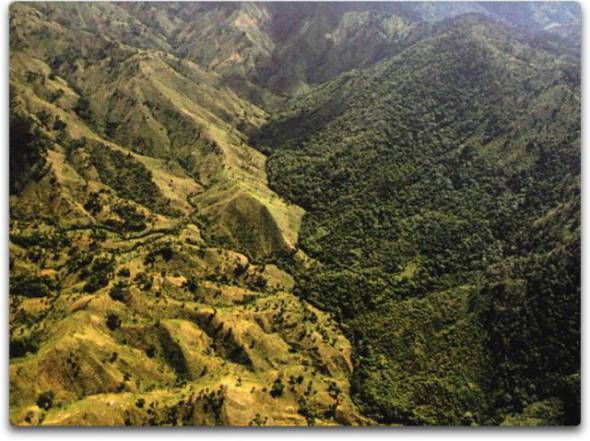

The

formula widely agreed upon by conservation scientists is to keep half the land

and half the sea of the planet as wild and protected from human intervention or

activity as possible. This conservation goal did not come out of the blue. Its

conception, called the Half-Earth Project, is an initiative led by a group of

biodiversity and conservation experts (I serve as one of the project’s lead

scientists). It builds on the theory of island biogeography, which I developed

with the mathematician Robert MacArthur in the 1960s.

Island

biogeography takes into account the size of an island and its distance from the

nearest island or mainland ecosystem to predict the number of species living

there; the more isolated an ecosystem, the fewer species it supports. After

much experimentation and a growing understanding of how this theory works, it

is being applied to the planning of conservation areas.

So how

do we know which places require protection under the definition of Half-Earth?

In general, three overlapping criteria have been suggested by scientists. They

are, first, areas judged best in number and rareness of species by experienced

field biologists; second, “hot spots,” localities known to support a large

number of species of a specific favored group such as birds and trees; and

third, broad-brush areas delineated by geography and vegetation, called

ecoregions.

All

three approaches are valuable, but applying them in too much haste can lead to

fatal error. They need an important underlying component to work — a more

thorough record of all of Earth’s existing species. Making decisions about land

protection without this fundamental knowledge would lead to irreversible

mistakes.

The

most striking fact about the living environment may be how little we know about

it. Even the number of living species can be only roughly calculated. A widely

accepted estimate by scientists puts the number at about 10 million. In

contrast, those formally described, classified and given two-part Latinized

names (Homo sapiens for humans, for example) number slightly more than two

million. With only about 20 percent of its species known and 80 percent

undiscovered, it is fair to call Earth a little-known planet.

Paleontologists

estimate that before the global spread of humankind the average rate of species

extinction was one species per million in each one- to 10-million-year

interval. Human activity has driven up the average global rate of extinction to

100 to 1,000 times that baseline rate. What ensues is a tragedy upon a tragedy:

Most species still alive will disappear without ever having been recorded. To

minimize this catastrophe, we must focus on which areas on land and in the sea

collectively harbor the most species.

Building

on new technologies, and on the insight and expertise of organizations and

individuals who have dedicated their lives the environment, the Half-Earth

Project is mapping the fine distribution of species across the globe to identify

the places where we can protect the highest number of species. By determining

which blocks of land and sea we can string together for maximum effect, we have

the opportunity to support the most biodiverse places in the world as well as

the people who call these paradises home. With the biodiversity of our planet

mapped carefully and soon, the bulk of Earth’s species, including humans, can

be saved.

By

necessity, global conservation areas will be chosen for what species they

contain, but in a way that will be supported, and not just tolerated, by the

people living within and around them. Property rights should not be abrogated.

The cultures and economies of indigenous peoples, who are de facto the original

conservationists, should be protected and supported. Community-based

conservation areas and management systems such as the National Natural

Landmarks Program, administered by the National Park Service, could serve as a

model.

To

effectively manage protected habitats, we must also learn more about all the species

of our planet and their interactions within ecosystems. By accelerating the

effort to discover, describe and conduct natural history studies for every one

of the eight million species estimated to exist but still unknown to science,

we can continue to add to and refine the Half-Earth Project map, providing

effective guidance for conservation to achieve our goal.

The

best-explored groups of organisms are the vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles,

amphibians, fishes), along with plants, especially trees and shrubs. Being

conspicuous, they are what we familiarly call “wildlife.” A great majority of

other species, however, are by far also the most abundant. I like to call them

“the little things that run the world.” They teem everywhere, in great number

and variety in and on all plants, throughout the soil at our feet and in the

air around us. They are the protists, fungi, insects, crustaceans, spiders,

pauropods, centipedes, mites, nematodes and legions of others whose scientific

names are seldom heard by the bulk of humanity. In the sea and along its shores

swarm organisms of the other living world — marine diatoms, crustaceans,

ascidians, sea hares, priapulids, coral, loriciferans and on through the still

mostly unfilled encyclopedia of life.

Do not

call these organisms “bugs” or “critters.” They too are wildlife. Let us learn

their correct names and care about their safety. Their existence makes possible

our own. We are wholly dependent on them.

With

new information technology and rapid genome mapping now available to us, the

discovery of Earth’s species can now be sped up exponentially. We can use

satellite imagery, species distribution analysis and other novel tools to

create a new understanding of what we must do to care for our planet. But there

is another crucial aspect to this effort: It must be supported by more “boots

on the ground,” a renaissance of species discovery and taxonomy led by field

biologists.

Within

one to three decades, candidate conservation areas can be selected with

confidence by construction of biodiversity inventories that list all of the

species within a given area. The expansion of this scientific activity will

enable global conservation while adding immense amounts of knowledge in biology

not achievable by any other means. By understanding our planet, we have the

opportunity to save it.

As we

focus on climate change, we must also act decisively to protect the living

world while we still have time. It would be humanity’s ultimate achievement.