This is longer than the usual post and so it will count for two posts and comments are due on or before Nov. 12, 2016

*****************************************

The controversy over genetically modified crops has long focused on

largely unsubstantiated fears that they are unsafe to eat.

But an extensive examination by The New York Times indicates that the debate

has missed a more basic problem — genetic modification in the United States and

Canada has not accelerated increases in crop yields or led to an overall reduction in

the use of chemical pesticides.

The promise of genetic modification was twofold: By making crops immune to

the effects of weedkillers and inherently resistant to many pests, they would grow so

robustly that they would become indispensable to feeding the world’s growing

population, while also requiring fewer applications of sprayed pesticides.

Twenty years ago, Europe largely rejected genetic modification at the same time

the United States and Canada were embracing it. Comparing results on the two

continents, using independent data as well as academic and industry research,

shows how the technology has fallen short of the promise.

An analysis by The Times using United Nations data showed that the United

States and Canada have gained no discernible advantage in yields — food per acre —when measured against Western Europe, a region with comparably modernized

agricultural producers like France and Germany. Also, a recent National Academy of

Sciences report found that “there was little evidence” that the introduction of

genetically modified crops in the United States had led to yield gains beyond those

seen in conventional crops.

At the same time, herbicide use has increased in the United States, even as major

crops like corn, soybeans and cotton have been converted to modified varieties. And

the United States has fallen behind Europe’s biggest producer, France, in reducing

the overall use of pesticides, which includes both herbicides and insecticides.

One measure, contained in data from the United States Geological Survey,

shows the stark difference in the use of pesticides. Since genetically modified crops

were introduced in the United States two decades ago for crops like corn, cotton and

soybeans, the use of toxins that kill insects and fungi has fallen by a third, but the

spraying of herbicides, which are used in much higher volumes, has risen by 21

percent.

By contrast, in France, use of insecticides and fungicides has fallen by a far

greater percentage — 65 percent — and herbicide use has decreased as well, by 36

percent.

Profound differences over genetic engineering have split Americans and

Europeans for decades. Although American protesters as far back as 1987 pulled up

prototype potato plants, European anger at the idea of fooling with nature has been

far more sustained. In the last few years, the March Against Monsanto has drawn

thousands of protesters in cities like Paris and Basel, Switzerland, and opposition to

G.M. foods is a foundation of the Green political movement. Still, Europeans eat

those foods when they buy imports from the United States and elsewhere.

Fears about the harmful effects of eating G.M. foods have proved to be largely

without scientific basis. The potential harm from pesticides, however, has drawn

researchers’ attention. Pesticides are toxic by design — weaponized versions, like

sarin, were developed in Nazi Germany — and have been linked to developmental

delays and cancer. “These chemicals are largely unknown,” said David Bellinger, a professor at the

Harvard University School of Public Health, whose research has attributed the loss

of nearly 17 million I.Q. points among American children 5 years old and under to

one class of insecticides. “We do natural experiments on a population,” he said,

referring to exposure to chemicals in agriculture, “and wait until it shows up as bad.”

The industry is winning on both ends — because the same companies make and

sell both the genetically modified plants and the poisons. Driven by these sales, the

combined market capitalizations of Monsanto, the largest seed company, and

Syngenta, the Swiss pesticide giant, have grown more than sixfold in the last decade

and a half. The two companies are separately involved in merger agreements that

would lift their new combined values to more than $100 billion each.

When presented with the findings, Robert T. Fraley, the chief technology officer

at Monsanto, said The Times had cherrypicked its data to reflect poorly on the

industry. “Every farmer is a smart businessperson, and a farmer is not going to pay

for a technology if they don’t think it provides a major benefit,” he said. “Biotech

tools have clearly driven yield increases enormously.”

Regarding the use of herbicides, in a statement, Monsanto said, “While overall

herbicide use may be increasing in some areas where farmers are following best

practices to manage emerging weed issues, farmers in other areas with different

circumstances may have decreased or maintained their herbicide usage.”

Genetically modified crops can sometimes be effective. Monsanto and others

often cite the work of Matin Qaim, a researcher at GeorgAugustUniversity of

Göttingen, Germany, including a metaanalysis of studies that he helped write

finding significant yield gains from genetically modified crops. But in an interview

and emails, Dr. Qaim said he saw significant effects mostly from insectresistant

varieties in the developing world, particularly in India.

“Currently available G.M. crops would not lead to major yield gains in Europe,”

he said. And regarding herbicideresistant crops in general: “I don’t consider this to

be the miracle type of technology that we couldn’t live without.”

A A Vow to Curb Chemicals

First came the Flavr Savr tomato in 1994, which was supposed to stay fresh

longer. The next year it was a small number of bugresistant russet potatoes. And by

1996, major genetically modified crops were being planted in the United States.

Monsanto, the most prominent champion of these new genetic traits, pitched

them as a way to curb the use of its pesticides. “We’re certainly not encouraging

farmers to use more chemicals,” a company executive told The Los Angeles Times in

1994. The next year, in a news release, the company said that its new gene for seeds,

named Roundup Ready, “can reduce overall herbicide use.”

Originally, the two main types of genetically modified crops were either

resistant to herbicides, allowing crops to be sprayed with weedkillers, or resistant to

some insects.

Figures from the United States Department of Agriculture show herbicide use

skyrocketing in soybeans, a leading G.M. crop, growing by two and a half times in

the last two decades, at a time when planted acreage of the crop grew by less than a

third. Use in corn was trending downward even before the introduction of G.M.

crops, but then nearly doubled from 2002 to 2010, before leveling off. Weed

resistance problems in such crops have pushed overall usage up.

To some, this outcome was predictable. The whole point of engineering bugresistant

plants “was to reduce insecticide use, and it did,” said Joseph Kovach, a

retired Ohio State University researcher who studied the environmental risks of

pesticides. But the goal of herbicideresistant seeds was to “sell more product,” he

said — more herbicide.

Farmers with crops overcome by weeds, or a particular pest or disease, can

understandably be G.M. evangelists. “It’s silly bordering on ridiculous to turn our

backs on a technology that has so much to offer,” said Duane Grant, the chairman of

the Amalgamated Sugar Company, a cooperative of more than 750 sugar beet

farmers in the Northwest. He says crops resistant to Roundup, Monsanto’s most popular weedkiller, saved

his cooperative.

But weeds are becoming resistant to Roundup around the world — creating an

opening for the industry to sell more seeds and more pesticides. The latest seeds

have been engineered for resistance to two weedkillers, with resistance to as many as

five planned. That will also make it easier for farmers battling resistant weeds to

spray a widening array of poisons sold by the same companies.

Growing resistance to Roundup is also reviving old, and contentious, chemicals.

One is 2,4D, an ingredient in Agent Orange, the infamous Vietnam War defoliant.

Its potential risks have long divided scientists and have alarmed advocacy groups.

Another is dicamba. In Louisiana, Monsanto is spending nearly $1 billion to

begin production of the chemical there. And even though Monsanto’s version is not

yet approved for use, the company is already selling seeds that are resistant to it —

leading to reports that some farmers are damaging neighbors’ crops by illegally

spraying older versions of the toxin.

HighTech Kernels

Two farmers, 4,000 miles apart, recently showed a visitor their corn seeds. The

farmers, Bo Stone and Arnaud Rousseau, are sixthgeneration tillers of the land.

Both use seeds made by DuPont, the giant chemical company that is merging with

Dow Chemical.

To the naked eye, the seeds looked identical. Inside, the differences are

profound.

In Rowland, N.C., near the South Carolina border, Mr. Stone’s seeds brim with

genetically modified traits. They contain Roundup Ready, a Monsantomade trait

resistant to Roundup, as well as a gene made by Bayer that makes crops impervious

to a second herbicide. A trait called Herculex I was developed by Dow and Pioneer,

now part of DuPont, and attacks the guts of insect larvae. So does YieldGard, made

by Monsanto. Another big difference: the price tag. Mr. Rousseau’s seeds cost about $85 for a

50,000seed bag. Mr. Stone spends roughly $153 for the same amount of biotech

seeds.

For farmers, doing without genetically modified crops is not a simple choice.

Genetic traits are not sold à la carte.

Mr. Stone, 45, has a master’s degree in agriculture and listens to Prime Country

radio in his Ford pickup. He has a test field where he tries out new seeds, looking for

characteristics that he particularly values — like plants that stand well, without

support.

“I’m choosing on yield capabilities and plant characteristics more than I am on

G.M.O. traits” like bug and poison resistance, he said, underscoring a crucial point:

Yield is still driven by breeding plants to bring out desirable traits, as it has been for

thousands of years.

That said, Mr. Stone values genetic modifications to reduce his insecticide use

(though he would welcome help with stink bugs, a troublesome pest for many

farmers). And Roundup resistance in pigweed has emerged as a problem.

“No G.M. trait for us is a silver bullet,” he said.

By contrast, at Mr. Rousseau’s farm in TrocyenMultien, a village outside Paris,

his corn has none of this engineering because the European Union bans most crops

like these.

“The door is closed,” says Mr. Rousseau, 42, who is vice president of one of

France’s many agricultural unions. His 840acre farm was a site of World War I

carnage in the Battle of the Marne.

As with Mr. Stone, Mr. Rousseau’s yields have been increasing, though they go

up and down depending on the year. Farm technology has also been transformative.

“My grandfather had horses and cattle for cropping,” Mr. Rousseau said. “I’ve got

tractors with motors.”He wants access to the same technologies as his competitors across the Atlantic,

and thinks G.M. crops could save time and money.

“Seen from Europe, when you speak with American farmers or Canadian

farmers, we’ve got the feeling that it’s easier,” Mr. Rousseau said. “Maybe it’s not

right. I don’t know, but it’s our feeling.”

Feeding the World

With the world’s population expected to reach nearly 10 billion by 2050,

Monsanto has long held out its products as a way “to help meet the food demands of

these added billions,” as it said in a 1995 statement. That remains an industry

mantra.

“It’s absolutely key that we keep innovating,” said Kurt Boudonck, who manages

Bayer’s sprawling North Carolina greenhouses. “With the current production

practices, we are not going to be able to feed that amount of people.”

But a broad yield advantage has not emerged. The Times looked at regional data

from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, comparing main

genetically modified crops in the United States and Canada with varieties grown in

Western Europe, a grouping used by the agency that comprises seven nations,

including the two largest agricultural producers, France and Germany.

For rapeseed, a variant of which is used to produce canola oil, The Times

compared Western Europe with Canada, the largest producer, over three decades,

including a period well before the introduction of genetically modified crops.

Despite rejecting genetically modified crops, Western Europe maintained a lead

over Canada in yields. While that is partly because different varieties are grown in

the two regions, the trend lines in the relative yields have not shifted in Canada’s

favor since the introduction of G.M. crops, the data shows.

For corn, The Times compared the United States with Western Europe. Over

three decades, the trend lines between the two barely deviate. And sugar beets, a

major source of sugar, have shown stronger yield growth recently in Western Europe than the United States, despite the dominance of genetically modified varieties over

the last decade.

Jack Heinemann, a professor at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand,

did a pioneering 2013 study comparing transAtlantic yield trends, using United

Nations data. Western Europe, he said, “hasn’t been penalized in any way for not

making genetic engineering one of its biotechnology choices.”

Biotech executives suggested making narrower comparisons. Dr. Fraley of

Monsanto highlighted data comparing yield growth in Nebraska and France, while

an official at Bayer suggested Ohio and France. These comparisons can be favorable

to the industry, while comparing other individual American states can be

unfavorable.

Michael Owen, a weed scientist at Iowa State University, said that while the

industry had long said G.M.O.s would “save the world,” they still “haven’t found the

mythical yield gene.”

Few New Markets

Battered by falling crop prices and consumer resistance that has made it hard to

win over new markets, the agrochemical industry has been swept by buyouts. Bayer

recently announced a deal to acquire Monsanto. And the stateowned China

National Chemical Corporation has received American regulatory approval to

acquire Syngenta, though Syngenta later warned the takeover could be delayed by

scrutiny from European authorities.

The deals are aimed at creating giants even more adept at selling both seeds and

chemicals. Already, a new generation of seeds is coming to market or in

development. And they have grand titles. There is the Bayer Balance GT Soybean

Performance System. Monsanto’s Genuity SmartStax RIB Complete corn. Dow’s

PhytoGen with Enlist and WideStrike 3 Insect Protection.

In industry jargon, they are “stacked” with many different genetically modified

traits. And there are more to come. Monsanto has said that the corn seed of 2025

will have 14 traits and allow farmers to spray five different kinds of herbicide. Newer genetically modified crops claim to do many things, such as protecting

against crop diseases and making food more nutritious. Some may be effective, some

not. To the industry, shifting crucial crops like corn, soybeans, cotton and rapeseed

almost entirely to genetically modified varieties in many parts of the world fulfills a

genuine need. To critics, it is a marketing opportunity.

“G.M.O. acceptance is exceptionally low in Europe,” said Liam Condon, the

head of Bayer’s crop science division, in an interview the day the Monsanto deal was

announced. He added: “But there are many geographies around the world where the

need is much higher and where G.M.O. is accepted. We will go where the market and

the customers demand our technology.” NYT 10/30/2016

This space is created for the benefit of the students registered in Eco 296U at Pace, Pleasantville NY.

Sunday, October 30, 2016

Friday, October 7, 2016

GMO: Pros and Cons

Comments due by Oct. 14, 2016 (#5)

Genetically modified organisms (GMO) are organisms made with engineered material with the goal of improving the original organism. They can then be used, in some cases, to produce GMO foods.

GMO seeds are used in 90 percent of corn, soybeans and cotton grown in the United States, according to the Center for Food Safety. To avoid eating foods that contain GMOs, look for labels that specify that fruits and vegetables is "organic" or "USDA Organic."

While GMOs come with known benefits to human health and the farming industry overall, there are some controversial negatives.

First the pros:

1. Seeds are genetically changed for multiple reasons, which include improving resistance to insects and generating healthier crops, according to Healthline.com. This can lower risk of crop failure, and make crops better resistant to extreme weather.

2. Engineering can also eliminate seeds and produce a longer shelf life, which allows for the "safe transport to people in countries without access to nutrition-rich foods."

3. Environmental benefits. Less chemicals, time, machinery, and land are needed for GMO crops and animals, which can help reduce environmental pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and soil erosion. Enhanced productivity because of GMOs could allow farmers to dedicate less real estate to crops. Also, farmers are already growing corn, cotton, and potatoes without spraying the bacterial insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis because the crops produce their own insecticides, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

4. Better nutrition. By modifying some GMO foods in terms of mineral or vitamin content, companies can supply more necessary nutrients and help fight worldwide malnutrition, according to The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. For example, vitamin A-enhanced rice, or "golden rice," is helping to reduce global vitamin A deficiencies.

5. The use of molecular biology in vaccination development has been successful and holds promise, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Scientists have engineered plants to produce vaccines, proteins, and other pharmaceutical goods in a process called "pharming."

Here are some negatives:

1. Food allergies in children under 18 spiked from 3.4 percent in 1997-99 to 5.1 percent in 2009-11, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, though it bears noting that there's no conclusive scientific link to GMO foods.

2. GMOs can pose significant allergy risks, according to a Brown University study. Genetic enhancements often combine proteins not contained in the original organism, which can cause allergic reactions for humans. For example, if a protein from an organism that caused an allergic reaction is added to something that previously didn't, it may prompt a new allergic reaction.

3. Lowered resistance to antibiotics. Some GMOs have built-in antibiotic qualities that enhance immunity, according to Iowa State University, but eating them can lessen the effectiveness of actual antibiotics.

4. Genes may migrate. According to The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, "Through 'gene escape,' they can pass on to other members of the same species and perhaps other species. Genes introduced in GMOs are no exception, and interactions might occur at gene, cell, plant, and ecosystem level. Problems could result if, for example, herbicide-resistance genes got into weeds. So far, research on this is inconclusive, with scientists divided — often bitterly. But there is scientific consensus that once widely released, recalling transgenes or foreign DNA sequences, whose safety is still subject to scientific debate, will not be feasible."

(Newsmax )

Friday, September 30, 2016

Sixth Extinction Crisis

Comments due by October 7, 2016

It’s frightening but true: Our planet is now in the midst of its sixth mass extinction of plants and animals — the sixth wave of extinctions in the past half-billion years. We’re currently experiencing the worst spate of species die-offs since the loss of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. Although extinction is a natural phenomenon, it occurs at a natural “background” rate of about one to five species per year. Scientists estimate we’re now losing species at 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate, with literally dozens going extinct every day [1]. It could be a scary future indeed, with as many as 30 to 50 percent of all species possibly heading toward extinction by mid-century [2].

Unlike past mass extinctions, caused by events like asteroid strikes, volcanic eruptions, and natural climate shifts, the current crisis is almost entirely caused by us — humans. In fact, 99 percent of currently threatened species are at risk from human activities, primarily those driving habitat loss, introduction of exotic species, and global warming [3]. Because the rate of change in our biosphere is increasing, and because every species’ extinction potentially leads to the extinction of others bound to that species in a complex ecological web, numbers of extinctions are likely to snowball in the coming decades as ecosystems unravel.

Species diversity ensures ecosystem resilience, giving ecological communities the scope they need to withstand stress. Thus while conservationists often justifiably focus their efforts on species-rich ecosystems like rainforests and coral reefs — which have a lot to lose — a comprehensive strategy for saving biodiversity must also include habitat types with fewer species, like grasslands, tundra, and polar seas — for which any loss could be irreversibly devastating. And while much concern over extinction focuses on globally lost species, most of biodiversity’s benefits take place at a local level, and conserving local populations is the only way to ensure genetic diversity critical for a species’ long-term survival.

In the past 500 years, we know of approximately 1,000 species that have gone extinct, from the woodland bison of West Virginia and Arizona’s Merriam’s elk to the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, passenger pigeon and Puerto Rico’s Culebra parrot — but this doesn’t account for thousands of species that disappeared before scientists had a chance to describe them [4]. Nobody really knows how many species are in danger of becoming extinct. Noted conservation scientist David Wilcove estimates that there are 14,000 to 35,000 endangered species in the United States, which is 7 to 18 percent of U.S. flora and fauna. The IUCN has assessed roughly 3 percent of described species and identified 16,928 species worldwide as being threatened with extinction, or roughly 38 percent of those assessed. In its latest four-year endangered species assessment, the IUCN reports that the world won’t meet a goal of reversing the extinction trend toward species depletion by 2010 [5].

In the past 500 years, we know of approximately 1,000 species that have gone extinct, from the woodland bison of West Virginia and Arizona’s Merriam’s elk to the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, passenger pigeon and Puerto Rico’s Culebra parrot — but this doesn’t account for thousands of species that disappeared before scientists had a chance to describe them [4]. Nobody really knows how many species are in danger of becoming extinct. Noted conservation scientist David Wilcove estimates that there are 14,000 to 35,000 endangered species in the United States, which is 7 to 18 percent of U.S. flora and fauna. The IUCN has assessed roughly 3 percent of described species and identified 16,928 species worldwide as being threatened with extinction, or roughly 38 percent of those assessed. In its latest four-year endangered species assessment, the IUCN reports that the world won’t meet a goal of reversing the extinction trend toward species depletion by 2010 [5].

What’s clear is that many thousands of species are at risk of disappearing forever in the coming decades.

Unlike past mass extinctions, caused by events like asteroid strikes, volcanic eruptions, and natural climate shifts, the current crisis is almost entirely caused by us — humans. In fact, 99 percent of currently threatened species are at risk from human activities, primarily those driving habitat loss, introduction of exotic species, and global warming [3]. Because the rate of change in our biosphere is increasing, and because every species’ extinction potentially leads to the extinction of others bound to that species in a complex ecological web, numbers of extinctions are likely to snowball in the coming decades as ecosystems unravel.

Species diversity ensures ecosystem resilience, giving ecological communities the scope they need to withstand stress. Thus while conservationists often justifiably focus their efforts on species-rich ecosystems like rainforests and coral reefs — which have a lot to lose — a comprehensive strategy for saving biodiversity must also include habitat types with fewer species, like grasslands, tundra, and polar seas — for which any loss could be irreversibly devastating. And while much concern over extinction focuses on globally lost species, most of biodiversity’s benefits take place at a local level, and conserving local populations is the only way to ensure genetic diversity critical for a species’ long-term survival.

In the past 500 years, we know of approximately 1,000 species that have gone extinct, from the woodland bison of West Virginia and Arizona’s Merriam’s elk to the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, passenger pigeon and Puerto Rico’s Culebra parrot — but this doesn’t account for thousands of species that disappeared before scientists had a chance to describe them [4]. Nobody really knows how many species are in danger of becoming extinct. Noted conservation scientist David Wilcove estimates that there are 14,000 to 35,000 endangered species in the United States, which is 7 to 18 percent of U.S. flora and fauna. The IUCN has assessed roughly 3 percent of described species and identified 16,928 species worldwide as being threatened with extinction, or roughly 38 percent of those assessed. In its latest four-year endangered species assessment, the IUCN reports that the world won’t meet a goal of reversing the extinction trend toward species depletion by 2010 [5].

In the past 500 years, we know of approximately 1,000 species that have gone extinct, from the woodland bison of West Virginia and Arizona’s Merriam’s elk to the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, passenger pigeon and Puerto Rico’s Culebra parrot — but this doesn’t account for thousands of species that disappeared before scientists had a chance to describe them [4]. Nobody really knows how many species are in danger of becoming extinct. Noted conservation scientist David Wilcove estimates that there are 14,000 to 35,000 endangered species in the United States, which is 7 to 18 percent of U.S. flora and fauna. The IUCN has assessed roughly 3 percent of described species and identified 16,928 species worldwide as being threatened with extinction, or roughly 38 percent of those assessed. In its latest four-year endangered species assessment, the IUCN reports that the world won’t meet a goal of reversing the extinction trend toward species depletion by 2010 [5].What’s clear is that many thousands of species are at risk of disappearing forever in the coming decades.

AMPHIBIANS

No group of animals has a higher rate of endangerment than amphibians. Scientists estimate that a third or more of all the roughly 6,300 known species of amphibians are at risk of extinction [6]. The current amphibian extinction rate may range from 25,039 to 45,474 times the background extinction rate [7].

Frogs, toads, and salamanders are disappearing because of habitat loss, water and air pollution, climate change, ultraviolet light exposure, introduced exotic species, and disease. Because of their sensitivity to environmental changes, vanishing amphibians should be viewed as the canary in the global coal mine, signaling subtle yet radical ecosystem changes that could ultimately claim many other species, including humans.

BIRDS

Birds occur in nearly every habitat on the planet and are often the most visible and familiar wildlife to people across the globe. As such, they provide an important bellwether for tracking changes to the biosphere. Declining bird populations across most to all habitats confirm that profound changes are occurring on our planet in response to human activities.

A 2009 report on the state of birds in the United States found that 251 (31 percent) of the 800 species in the country are of conservation concern [8]. Globally, BirdLife International estimates that 12 percent of known 9,865 bird species are now considered threatened, with 192 species, or 2 percent, facing an “extremely high risk” of extinction in the wild — two more species than in 2008. Habitat loss and degradation have caused most of the bird declines, but the impacts of invasive species and capture by collectors play a big role, too.

FISH

Increasing demand for water, the damming of rivers throughout the world, the dumping and accumulation of various pollutants, and invasive species make aquatic ecosystems some of the most threatened on the planet; thus, it’s not surprising that there are many fish species that are endangered in both freshwater and marine habitats.

The American Fisheries Society identified 700 species of freshwater or anadromous fish in North America as being imperiled, amounting to 39 percent of all such fish on the continent [9]. In North American marine waters, at least 82 fish species are imperiled. Across the globe, 1,851 species of fish — 21 percent of all fish species evaluated — were deemed at risk of extinction by the IUCN in 2010, including more than a third of sharks and rays.

INVERTEBRATES

Invertebrates, from butterflies to mollusks to earthworms to corals, are vastly diverse — and though no one knows just how many invertebrate species exist, they’re estimated to account for about 97 percent of the total species of animals on Earth [10]. Of the 1.3 million known invertebrate species, the IUCN has evaluated about 9,526 species, with about 30 percent of the species evaluated at risk of extinction. Freshwater invertebrates are severely threatened by water pollution, groundwater withdrawal, and water projects, while a large number of invertebrates of notable scientific significance have become either endangered or extinct due to deforestation, especially because of the rapid destruction of tropical rainforests. In the ocean, reef-building corals are declining at an alarming rate: 2008’s first-ever comprehensive global assessment of these animals revealed that a third of reef-building corals are threatened.

MAMMALS

Perhaps one of the most striking elements of the present extinction crisis is the fact that the majority of our closest relatives — the primates — are severely endangered. About 90 percent of primates — the group that contains monkeys, lemurs, lorids, galagos, tarsiers, and apes (as well as humans) — live in tropical forests, which are fast disappearing. The IUCN estimates that almost 50 percent of the world’s primate species are at risk of extinction. Overall, the IUCN estimates that half the globe’s 5,491 known mammals are declining in population and a fifth are clearly at risk of disappearing forever with no less than 1,131 mammals across the globe classified as endangered, threatened, or vulnerable. In addition to primates, marine mammals — including several species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises — are among those mammals slipping most quickly toward extinction.

PLANTS

Through photosynthesis, plants provide the oxygen we breathe and the food we eat and are thus the foundation of most life on Earth. They’re also the source of a majority of medicines in use today. Of the more than 300,000 known species of plants, the IUCN has evaluated only 12,914 species, finding that about 68 percent of evaluated plant species are threatened with extinction.

Unlike animals, plants can’t readily move as their habitat is destroyed, making them particularly vulnerable to extinction. Indeed, one study found that habitat destruction leads to an “extinction debt,” whereby plants that appear dominant will disappear over time because they aren’t able to disperse to new habitat patches [11]. Global warming is likely to substantially exacerbate this problem. Already, scientists say, warming temperatures are causing quick and dramatic changes in the range and distribution of plants around the world. With plants making up the backbone of ecosystems and the base of the food chain, that’s very bad news for all species, which depend on plants for food, shelter, and survival.

REPTILES

Globally, 21 percent of the total evaluated reptiles in the world are deemed endangered or vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN — 594 species — while in the United States, 32 reptile species are at risk, about 9 percent of the total. Island reptile species have been dealt the hardest blow, with at least 28 island reptiles having died out since 1600. But scientists say that island-style extinctions are creeping onto the mainlands because human activities fragment continental habitats, creating “virtual islands” as they isolate species from one another, preventing interbreeding and hindering populations’ health. The main threats to reptiles are habitat destruction and the invasion of nonnative species, which prey on reptiles and compete with them for habitat and food.

No group of animals has a higher rate of endangerment than amphibians. Scientists estimate that a third or more of all the roughly 6,300 known species of amphibians are at risk of extinction [6]. The current amphibian extinction rate may range from 25,039 to 45,474 times the background extinction rate [7].

Frogs, toads, and salamanders are disappearing because of habitat loss, water and air pollution, climate change, ultraviolet light exposure, introduced exotic species, and disease. Because of their sensitivity to environmental changes, vanishing amphibians should be viewed as the canary in the global coal mine, signaling subtle yet radical ecosystem changes that could ultimately claim many other species, including humans.

BIRDS

Birds occur in nearly every habitat on the planet and are often the most visible and familiar wildlife to people across the globe. As such, they provide an important bellwether for tracking changes to the biosphere. Declining bird populations across most to all habitats confirm that profound changes are occurring on our planet in response to human activities.

A 2009 report on the state of birds in the United States found that 251 (31 percent) of the 800 species in the country are of conservation concern [8]. Globally, BirdLife International estimates that 12 percent of known 9,865 bird species are now considered threatened, with 192 species, or 2 percent, facing an “extremely high risk” of extinction in the wild — two more species than in 2008. Habitat loss and degradation have caused most of the bird declines, but the impacts of invasive species and capture by collectors play a big role, too.

FISH

Increasing demand for water, the damming of rivers throughout the world, the dumping and accumulation of various pollutants, and invasive species make aquatic ecosystems some of the most threatened on the planet; thus, it’s not surprising that there are many fish species that are endangered in both freshwater and marine habitats.

The American Fisheries Society identified 700 species of freshwater or anadromous fish in North America as being imperiled, amounting to 39 percent of all such fish on the continent [9]. In North American marine waters, at least 82 fish species are imperiled. Across the globe, 1,851 species of fish — 21 percent of all fish species evaluated — were deemed at risk of extinction by the IUCN in 2010, including more than a third of sharks and rays.

INVERTEBRATES

Invertebrates, from butterflies to mollusks to earthworms to corals, are vastly diverse — and though no one knows just how many invertebrate species exist, they’re estimated to account for about 97 percent of the total species of animals on Earth [10]. Of the 1.3 million known invertebrate species, the IUCN has evaluated about 9,526 species, with about 30 percent of the species evaluated at risk of extinction. Freshwater invertebrates are severely threatened by water pollution, groundwater withdrawal, and water projects, while a large number of invertebrates of notable scientific significance have become either endangered or extinct due to deforestation, especially because of the rapid destruction of tropical rainforests. In the ocean, reef-building corals are declining at an alarming rate: 2008’s first-ever comprehensive global assessment of these animals revealed that a third of reef-building corals are threatened.

MAMMALS

Perhaps one of the most striking elements of the present extinction crisis is the fact that the majority of our closest relatives — the primates — are severely endangered. About 90 percent of primates — the group that contains monkeys, lemurs, lorids, galagos, tarsiers, and apes (as well as humans) — live in tropical forests, which are fast disappearing. The IUCN estimates that almost 50 percent of the world’s primate species are at risk of extinction. Overall, the IUCN estimates that half the globe’s 5,491 known mammals are declining in population and a fifth are clearly at risk of disappearing forever with no less than 1,131 mammals across the globe classified as endangered, threatened, or vulnerable. In addition to primates, marine mammals — including several species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises — are among those mammals slipping most quickly toward extinction.

PLANTS

Through photosynthesis, plants provide the oxygen we breathe and the food we eat and are thus the foundation of most life on Earth. They’re also the source of a majority of medicines in use today. Of the more than 300,000 known species of plants, the IUCN has evaluated only 12,914 species, finding that about 68 percent of evaluated plant species are threatened with extinction.

Unlike animals, plants can’t readily move as their habitat is destroyed, making them particularly vulnerable to extinction. Indeed, one study found that habitat destruction leads to an “extinction debt,” whereby plants that appear dominant will disappear over time because they aren’t able to disperse to new habitat patches [11]. Global warming is likely to substantially exacerbate this problem. Already, scientists say, warming temperatures are causing quick and dramatic changes in the range and distribution of plants around the world. With plants making up the backbone of ecosystems and the base of the food chain, that’s very bad news for all species, which depend on plants for food, shelter, and survival.

REPTILES

Globally, 21 percent of the total evaluated reptiles in the world are deemed endangered or vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN — 594 species — while in the United States, 32 reptile species are at risk, about 9 percent of the total. Island reptile species have been dealt the hardest blow, with at least 28 island reptiles having died out since 1600. But scientists say that island-style extinctions are creeping onto the mainlands because human activities fragment continental habitats, creating “virtual islands” as they isolate species from one another, preventing interbreeding and hindering populations’ health. The main threats to reptiles are habitat destruction and the invasion of nonnative species, which prey on reptiles and compete with them for habitat and food.

Friday, September 23, 2016

Is it safe to extract the coal and oil already discovered?

Comments due by September 30, 2016 (# 3)

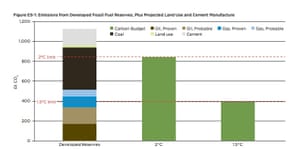

The world’s working coal mines and oil and gas fields contain enough carbon to push the world beyond the threshold for catastrophic climate change, according to a report released on Thursday.

If all the existing fuel were to be burned, projects currently operating or under construction could be expected to release 942Gt CO2, said the report by US-based thinktank Oil Change International (OCI).

This exceeds the carbon limits that would most likely warm the world 1.5C and even over 2C above the pre-industrial average. These were limits agreed at last year’s climate conference in Paris.

It has been established for some time that the enormous unworked reserves claimed by fossil fuel companies contain vastly too much carbon to ever be burned safely. But OCI said that this was the first time an analysis had been done of how much greenhouse gas is stored in projects already working or under construction.

Founder of 350.org and climate campaign Bill McKibben said the report “change[d] our understanding of where we stand. Profoundly”.

It means that even if not a single new coal mine, oil or gas field were opened up, the carbon budget would be at risk, said OCI’s executive director Stephen Kretzmann.

Projected investment in new extraction sites and infrastructure over the next 20 years adds up to a staggering US$14tn, the report found.

“Continued expansion of the fossil fuel industry is now quite clearly and quantifiably climate denial,” said Kretzmann.

The OCI report said existing oil and gas fields alone would exceed the carbon budget for 1.5C – which is a limit some small island states say would finish them and scientists believe would wipe out most coral reefs.

James Leaton, research director at the Carbon Tracker thinktank which did much to popularise the concept of “unburnable carbon”, said research by Carbon Tracker in 2015 showed coal demand was declining so quickly that current reserves would be enough. But the picture was less clear for oil and gas.

“There is clearly no need for new coal mines to be developed if we are to stay within a 2C carbon budget,” said Leaton. “Because oil and gas production declines over time in any particular well, this may fall faster than the level of oil and gas demand in [a 2C scenario], in which case some new production would be needed. Depending on how much carbon budget you allocate to each fossil fuel, and the speed of the energy transition assumed, the window for new oil and gas will also start to close.”

In the UK, the government has committed to opening its shale gas resources to fracking. Ken Cronin, chief executive of the industry body UK Onshore Oil and Gas, said: “This report needs to look more deeply into the use of gas in a modern energy mix, looking at areas such as reformation of methane into hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, particularly for heating systems and potentially transport. The simple fact is that the best way to combat climate change is to remove coal ASAP and to do that you need to replace much of the coal capacity with gas.”

The OCI report did not take into account carbon capture and storage (CCS), which it argued is still at an “uncertain” stage of development. The International Energy Agency reported last week that CCS, which is fitted to emissions sources to trap carbon, was being rolled out at a rate of just one project every year.

Study author Greg Muttitt said it was imperative for governments to focus on shutting down new mines and fields before a sod was turned.

“Once an extraction operation is underway, it creates an incentive to continue so as to recoup investment and create profit, ensuring the product – the fossil fuels – are extracted and burned. These incentives are powerful, and the industry will do whatever it takes to protect their investments and keep drilling,” he said.

There is new carbon math coming tomorrow that will change our understanding of where we stand. Profoundly.

Ben Caldecott, director of the Sustainable Finance Programme at the University of Oxford Smith School said: “One direct implication of meeting climate targets are stranded upstream fossil fuel assets. These stranded assets need to be managed, particularly in terms of the communities that could be negatively impacted. Policymakers need to proactively manage these impacts to ensure a ‘just transition’.”

The report expands on a call made by former Kiribati president Anote Tong last year to stop opening new coal mines. China, the US and Indonesia, the world’s largest, third- and fifth-largest coal producers, have banned any new coal mines. In the US, the moratorium is only on public land.

But in Australia’s Galilee basin, there are nine proposed coal mines with a total lifetime emissions of 24Gt CO2. This includes the massive Adani Carmichael mine, which the Australian government has approved. The Australian Department of Environment would not comment on whether it had assessed the impact of the Carmichael mine on the global carbon budget.

Friday, September 16, 2016

Economic Growth and Sustainability

Comments due by Sept. 23, 2016

– Until recently, the usual thinking among macroeconomists has been that short-term weather fluctuations don’t matter much for economic activity. Construction hiring may be stronger than usual in a March when the weather is unseasonably mild, but there will be payback in April and May. If heavy rains discourage people from shopping in August, they will just spend more in September.

– Until recently, the usual thinking among macroeconomists has been that short-term weather fluctuations don’t matter much for economic activity. Construction hiring may be stronger than usual in a March when the weather is unseasonably mild, but there will be payback in April and May. If heavy rains discourage people from shopping in August, they will just spend more in September.

But recent economic research, bolstered by an exceptionally strong El Niño – a complex global climactic event marked by exceptionally warm Pacific Ocean water off the coast of Ecuador and Peru – has prompted a rethink of this view.

German Europe or European Germany?

Hugo Drochon poses the question that Europe and the world can no longer avoid, and examines how Joschka Fischer, Otmar Issing, Anne-Marie Slaughter, and others address it.

Extreme weather certainly throws a ringer into key short-term macroeconomic statistics. It can add or subtract 100,000 jobs to monthly US employment, the single most-watched economic statistic in the world, and generally thought to be one of the most accurate. The impact of El Niño-related weather events like the one this year (known more precisely as “El Niño Southern Oscillation” events) can be especially large because of their global reach.

Recent research from the International Monetary Fund suggests that countries such as Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, and South Africa suffer adversely in El Niño years (often due to droughts), whereas some regions, including the United States, Canada, and Europe, can benefit. California, for example, which has been experiencing years of severe drought, is finally getting rain. Generally, but not always, El Niño events tend to be inflationary, in part because low crop yields lead to higher prices.

After two crazy winters in Boston, where I live, it would be hard to convince people that weather doesn’t matter. Last year, the city experienced the largest snow accumulationon record. Eventually, there was no longer any place to put it: four-lane highways narrowed to two lanes, and two-lane roads to one. Roofs collapsed and “ice dams” building up from gutters caused severe flooding. Public transport closed, and many people couldn’t get to their jobs. It was a slow-motion natural catastrophe that lasted for months.

The US as a whole did not have a winter as extreme as New England’s in the first part of 2015, and the effects of the weather on the country’s overall economy were subdued. True, New York City had some significant snowfalls; but no one would have paid much attention had the mayor been more competent in getting the streets plowed. Eastern Canada suffered much more, with severe winter weather playing a role (along with lower commodity prices) in the country’s mini-recession in the first half of the year.

This year’s winter is the polar opposite of last year’s. It was 68º Fahrenheit (20º Celsius) at Boston’s Logan Airport the day before Christmas, and the first speck of snow didn’t come until just before New Year’s Day. Trees and plants, sensing spring, started to blossom; birds were just as confused.

Last winter Boston was something of an anomaly. This year, thanks in part to El Niño, weird weather is the new normal. From Russia to Switzerland, temperatures have been elevated by 4-5º Celsius, and the weather patterns look set to remain highly unusual in 2016.

The effect on developing countries is of particular concern, because many are already reeling from the negative impact of China’s slowdown on commodity prices, and because drought conditions could lead to severe crop shortfalls. The last severe El Niño, in 1997-1998, which some called the “El Niño of the Century,” represented a huge setback for many developing countries.

The economic effects of El Niño events are almost as complex as the underlying weather phenomenon itself and therefore are difficult to predict. When we look back on 2016, however, it is quite possible that El Niño will be regarded as one of the major drivers of economic performance in many key countries, with Zimbabwe and South Africa facing drought and food crises, and Indonesia struggling with forest fires. In the American Midwest, there has lately been massive flooding.

There is a long history of weather having a profound impact on civil strife as well. Economist Emily Oster has argued that the biggest spikes in witch burnings in the Middle Ages, in which hundreds of thousands (mostly women) were killed, came during periods of economic deprivation and apparently weather-related food shortages. Some have traced the roots of the civil war in Syria to droughts that led to severe crop failure and forced a mass inflow of farmers to the cities.

On a more mundane level (but highly consequential economically), the warm weather in the US may very well cloud the job numbers the Federal Reserve uses in deciding when to raise interest rates. It is true that employment data are already seasonally adjusted to allow for normal weather differences in temperate zones; construction is always higher during spring than winter. But standard seasonal adjustments do not account for major weather deviations.

Overall, the evidence from past El Niños suggests that the current massive one is likely to leave a significant footprint on global growth, helping support economic recovery in the US and Europe, while putting even more pressure on already weak emerging markets. It is not yet global warming, but it is already a very significant event economically – and perhaps just a taste of what is to come.

(Rogoff/Project Syndicate)

Tuesday, September 6, 2016

Green Economy

Comments due by 9/16/2016

Sustainable development has been the overarching goal of the international community since the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992. Amongst numerous commitments, the Conference called upon governments to develop national strategies for sustainable development, incorporating policy measures outlined in the Rio Declaration and Agenda 21. Despite the efforts of many governments around the world to implement such strategies as well as international cooperation to support national governments, there are continuing concerns over global economic and environmental developments in many countries. These have been intensified by recent prolonged global energy, food and financial crises, and underscored by continued warnings from global scientists that society is in danger of transgressing a number of planetary boundaries or ecological limits.

Despite the growing international interest in green economy, negotiations between Member States on the concept in the lead up to Rio+20 were challenging. This was partly due to the lack of an internationally agreed definition or universal principles for green economy, the emergence of interrelated but different terminology and concepts over recent years (such as green growth, low carbon development, sustainable economy, steady-state economy etc.), a lack of clarity around what green economy policy measures encompass and how they integrate with national priorities and objectives relating to economic growth and poverty eradication, as well as a perceived lack of experience in designing, implementing and reviewing the costs and benefits of green economy policies.

Friday, April 17, 2015

Cap and Trade :Ontarior

Comments due by April 25, 2015

Canada's provinces are taking command of the nation's battle against climate change, seizing the initiative from a reluctant federal government as the clock ticks down to a crucial international climate agreement later this year.

Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne on Monday signed a historic deal to join Quebec's cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions, while British Columbia Premier Christy Clark was invited to promote her province's carbon tax at the World Bank – an honour not usually accorded to a provincial leader.

And on Tuesday, Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard will play host to a meeting of provincial and territorial leaders to start crafting a national strategy to co-ordinate further climate action across the country.

"Climate change is one of the greatest challenges humankind has ever faced. This is about preserving a world for our children and our grandchildren," Ms. Wynne told reporters after meeting Mr. Couillard in his office near the National Assembly. "We cannot wait for a particular moment when the federal government decides it is going to engage."

Many of the details in Ontario's cap-and-trade system still have to be worked out over the next six months, but it is likely to look similar to the joint system run by Quebec and California. In that model, the government sets a cap on emissions and hands out some permits to industry for free while auctioning others off. The proceeds are then plowed back into other green programs, such as public transit.

Once Ontario's system is operating, 62 per cent of Canada's population and more than half its economy will be under the same carbon market. Including B.C., which uses a carbon tax instead, some three quarters of Canadians will be covered by provincial-level carbon pricing.

Ms. Clark on Monday said her message to leaders at the World Bank, which she will address Friday in Washington, will be to match B.C.'s success in slashing emissions through the tax: "The climate action challenge we're making to other governments is clear and simple: meet it or beat it."

While the federal government is moving forward with some climate-change measures – such as new regulations to make trucks more fuel efficient, and a plan to phase out coal-fired power generation – Ottawa has adamantly refused to support carbon pricing.

"We are very clear we don't want ... what is effectively a tax on carbon which would increase the cost for consumers and on taxpayers – the cost of electricity, of gasoline, of groceries," Finance Minister Joe Oliver told reporters Monday in response to Ontario and Quebec's deal. "We think this would be negative for the economy; it would be negative for consumers and for taxpayers. And that's why we oppose it."

The federal government is also leaving it up to the provinces to set their own emissions targets and report them to Ottawa, rather than attempting to forge a national strategy.

Mr. Couillard lamented this Monday, arguing that the federal government should negotiate with the provinces to set a clear plan that spells out exactly how much each province will cut in terms of emissions, and what each will do to achieve these targets.

The government must table its emission-reduction targets ahead of the UN climate summit in Paris in December, which will pull together an international accord for cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

"[The federal government should help with] getting to Paris with a common, well-documented position, which would include the global target for Canada and the allocation for different regions," Mr. Couillard said.

In the absence of the federal government, the provinces will be attempting to co-ordinate this themselves Tuesday.

But a spokesman for Environment Minister Leona Aglukkaq said Ottawa is attempting to work with the provinces and has received little feedback.

Ms. Aglukkaq has sent two letters to her provincial counterparts – one in November and another on Sunday – asking them to lay out their targets and plans beyond 2020. She told her colleagues the federal government will use that information, plus its own plans to regulate, to build a national submission for Paris.

However, Ottawa has rejected calls to lead a national negotiation on climate and energy policies and regional burden-sharing.

There are still major hurdles. Oil-rich Alberta, whose emissions are growing by leaps and bounds, must take tougher action to cut carbon if Canada is to achieve a net reduction over all. But Premier Jim Prentice, in the middle of a provincial election campaign, is skipping the Quebec meeting, leaving his province's plans up in the air.

Ms. Wynne, meanwhile, took a drubbing from the provincial opposition over her plan. Progressive Conservative environment critic Lisa Thompson argued that all cap-and-trade will do is make life more expensive for consumers in order to direct money into the treasury; she declared the plan a "new revenue tool to cover their wasteful spending."

Ms. Wynne appeared to anticipate this argument, and hit back at it as she unveiled the cap-and-trade plan at ecobee, a green-tech company in downtown Toronto, before flying to Quebec for her meeting with Mr. Couillard.

"When my granddaughter, Olivia, looks at me and says 'Grandma, what did you do [on climate change], I am not going to say to her 'I put my head in the sand because I was worried that maybe there would be a cost somewhere that I couldn't explain,'" she said. "I'm not going to do that."

(The Globe and Mail April 12, 2015)

Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne on Monday signed a historic deal to join Quebec's cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions, while British Columbia Premier Christy Clark was invited to promote her province's carbon tax at the World Bank – an honour not usually accorded to a provincial leader.

And on Tuesday, Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard will play host to a meeting of provincial and territorial leaders to start crafting a national strategy to co-ordinate further climate action across the country.

"Climate change is one of the greatest challenges humankind has ever faced. This is about preserving a world for our children and our grandchildren," Ms. Wynne told reporters after meeting Mr. Couillard in his office near the National Assembly. "We cannot wait for a particular moment when the federal government decides it is going to engage."

Many of the details in Ontario's cap-and-trade system still have to be worked out over the next six months, but it is likely to look similar to the joint system run by Quebec and California. In that model, the government sets a cap on emissions and hands out some permits to industry for free while auctioning others off. The proceeds are then plowed back into other green programs, such as public transit.

Once Ontario's system is operating, 62 per cent of Canada's population and more than half its economy will be under the same carbon market. Including B.C., which uses a carbon tax instead, some three quarters of Canadians will be covered by provincial-level carbon pricing.

Ms. Clark on Monday said her message to leaders at the World Bank, which she will address Friday in Washington, will be to match B.C.'s success in slashing emissions through the tax: "The climate action challenge we're making to other governments is clear and simple: meet it or beat it."

While the federal government is moving forward with some climate-change measures – such as new regulations to make trucks more fuel efficient, and a plan to phase out coal-fired power generation – Ottawa has adamantly refused to support carbon pricing.

"We are very clear we don't want ... what is effectively a tax on carbon which would increase the cost for consumers and on taxpayers – the cost of electricity, of gasoline, of groceries," Finance Minister Joe Oliver told reporters Monday in response to Ontario and Quebec's deal. "We think this would be negative for the economy; it would be negative for consumers and for taxpayers. And that's why we oppose it."

The federal government is also leaving it up to the provinces to set their own emissions targets and report them to Ottawa, rather than attempting to forge a national strategy.

Mr. Couillard lamented this Monday, arguing that the federal government should negotiate with the provinces to set a clear plan that spells out exactly how much each province will cut in terms of emissions, and what each will do to achieve these targets.

The government must table its emission-reduction targets ahead of the UN climate summit in Paris in December, which will pull together an international accord for cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

"[The federal government should help with] getting to Paris with a common, well-documented position, which would include the global target for Canada and the allocation for different regions," Mr. Couillard said.

In the absence of the federal government, the provinces will be attempting to co-ordinate this themselves Tuesday.

But a spokesman for Environment Minister Leona Aglukkaq said Ottawa is attempting to work with the provinces and has received little feedback.

Ms. Aglukkaq has sent two letters to her provincial counterparts – one in November and another on Sunday – asking them to lay out their targets and plans beyond 2020. She told her colleagues the federal government will use that information, plus its own plans to regulate, to build a national submission for Paris.

However, Ottawa has rejected calls to lead a national negotiation on climate and energy policies and regional burden-sharing.

There are still major hurdles. Oil-rich Alberta, whose emissions are growing by leaps and bounds, must take tougher action to cut carbon if Canada is to achieve a net reduction over all. But Premier Jim Prentice, in the middle of a provincial election campaign, is skipping the Quebec meeting, leaving his province's plans up in the air.

Ms. Wynne, meanwhile, took a drubbing from the provincial opposition over her plan. Progressive Conservative environment critic Lisa Thompson argued that all cap-and-trade will do is make life more expensive for consumers in order to direct money into the treasury; she declared the plan a "new revenue tool to cover their wasteful spending."

Ms. Wynne appeared to anticipate this argument, and hit back at it as she unveiled the cap-and-trade plan at ecobee, a green-tech company in downtown Toronto, before flying to Quebec for her meeting with Mr. Couillard.

"When my granddaughter, Olivia, looks at me and says 'Grandma, what did you do [on climate change], I am not going to say to her 'I put my head in the sand because I was worried that maybe there would be a cost somewhere that I couldn't explain,'" she said. "I'm not going to do that."

(The Globe and Mail April 12, 2015)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)