Comments due by April 20, 2018

Water inequality is increasing in the world’s

most environmentally stressed nations, warn the authors of a report that shows more than 800 million

people need to travel and queue for at least 30 minutes to access safe

supplies.

Despite an overall increase in provision of

tap water, the study - the State of the World’s Water 2018

- charts the gaps within and between nations, as poor communities face

competition over aquifers and rivers with agriculture and factories producing

goods for wealthier consumers.

While recent headlines have focused on

the drought in Cape Town, the NGO WaterAid, which

published the report on Wednesday, noted that communities in many other regions

have long been used to queues and limited supplies.

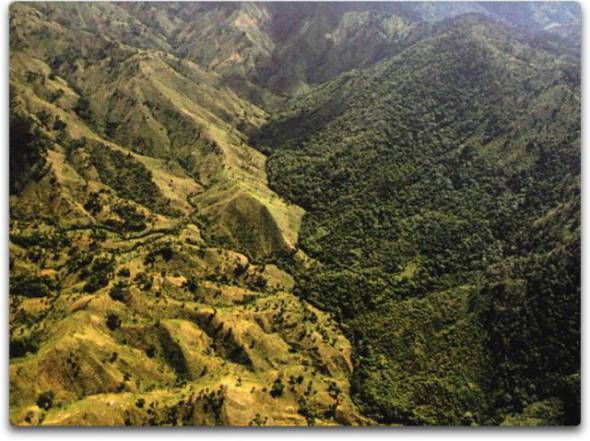

By far the worst affected country is Eritrea,

where only 19% of the population have basic access to water. It is followed by

Papua New Guinea, Uganda, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and

Somalia, all of which have rates of between 37% and 40%. It is no coincidence

that many of these nations have large numbers of refugees living in temporary

shelters.

Within countries, there is also considerable

variation linked to income and other factors. In Niger, only 41% of the poorest

people have access to water, while 72% of its wealthiest do. In neighbouring

Mali, 45% of the poor have access to water, compared to 93% of the rich.

“Inequality in access to water is growing

primarily as a result of a lack of political will,” said Lisa Schechtman, the

director of policy and advocacy for WaterAid.

“There is a risk of leaving people behind,

particularly in remote rural areas and among displaced communities.”

Most vulnerable are the old, sick, disabled

and displaced people in remote or rural locations.

Gender is also a key factor because woman bear

the brunt of the burden of collecting water. The time-consuming task of

fetching the UN-recommended 50-litres per day for a family of four takes the

equivalent of two and half months each year, the report says.

Collecting water time in school and raises the

risks of disease. Children are often the victims, with close to 289,000 dying

each year from diarrhoeal illnesses related to poor sanitation.

There have been improvements. The proportion

of the world’s population with access to clean water near their home has risen

from 81% to 89% since 2000. But this leaves 844 million people with a journey

and queues of at least 30 minutes to a safe source.

The greatest progress has been seen in big,

fast-growing developing nations. China has seen an extra 334 million people get

access to water between 2000 and 2015, followed by India with 301 million.

The biggest proportional gain was in

Afghanistan, where a post-war reconstruction effort raised the proportion of

people with access to water from 27% to 62% since 2000. Laos, Yemen, Mozambique

and Mali have also seen rapid progress.

However, the report notes the world still has

much work to do to achieve the UN’s sustainable development goal 6, which is to

provide safe water and sanitation to everyone by 2030.

This summer, world leaders will meet in New

York to review progress on this and other development targets.

To close this gap, WaterAid is calling for

more tax revenue to be mobilised to provide water for the poorest, improved

environmental management and support for people who speak out on the

UN-recognised right to safe drinking supplies and sanitation.

The problem of access is increasingly

complicated by climate change, pollution and a growing global population.

A separate report by the UN earlier this

week forecast that 5 billion people could face shortages for at least one month

a year by 2050.

Jonathan Farr, WaterAid’s senior policy

analyst on water security and climate change, said recent droughts highlighted

how extreme weather is adding to water stress on the poorest. “Cape Town is a

wake-up call, reminding us that access to water, our most precious resource, is

increasingly under threat.

“Those marginalised by age, gender, class,

caste or disability, or living in a slum or remote rural community, are hardest

to reach and will continue to suffer as long as governments do not prioritise

and fund access to water for all, and while disproportionate use of water by

industry and agriculture continues.”